'As Uganda, we need to reconfigure our social protection systems'

23rd February 2025

Studies have shown that the investment in social protection has benefits at household, community and national levels.

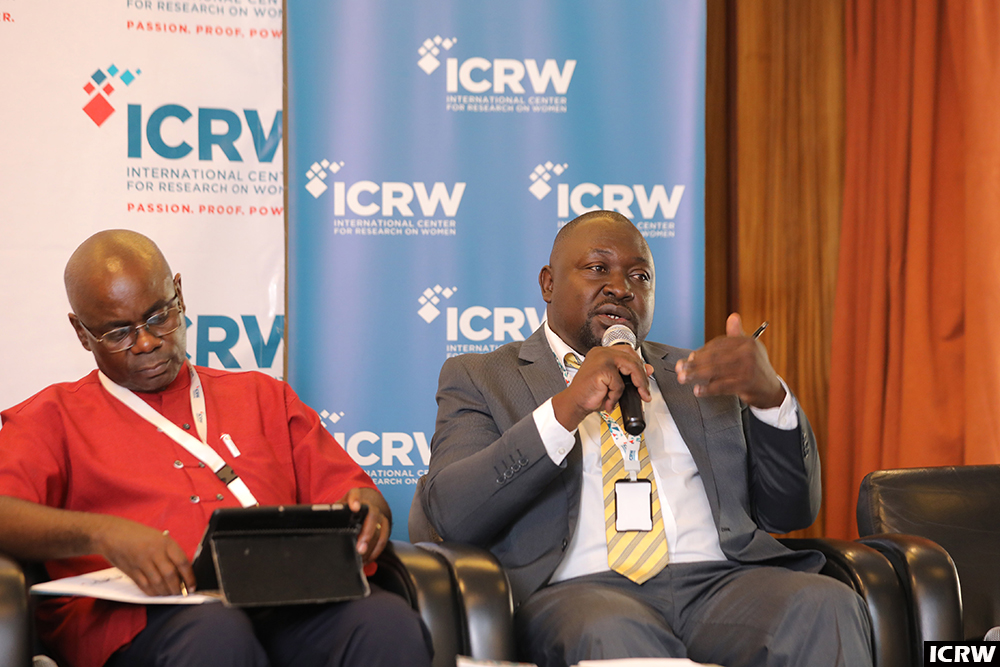

Paul Onapa (R), the deputy head of the Expanding Social Protection Programme at the gender ministry, speaks during a roundtable dialogue on the state of social protection in Uganda organized by International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW) on February 21, 2025 in Kampala. (Credit: ICRW)

Joseph Kizza

Senior Producer - Digital Content @New Vision

_____________________

SOCIAL PROTECTION

Every morning, whenever teenage mother-of-one Jane (pseudonym) leaves her one-roomed home for routine informal work, she steps out into a world of uncertainty, just like millions of other vulnerable people like her.

For one, the 17-year-old should be busy in school now — somewhere in her native Amuru district in Uganda’s north. But she is not.

The death of her widowed mother in mid-2019 forced Jane — an only child — out of school, two years shy of reaching Primary Seven.

Orphaned and desperately clueless thereafter, reality spat her out into the unfamiliar world of Kampala — albeit thankfully into the open hands of her city-based aunt, a roadside vendor of ‘bogoya’ (yellow bananas).

Under her guidance, Jane quickly learned the ropes and two years after first setting foot in Uganda's capital, she was streetwise enough to move out to start a life of independence in Kitetika, a village off Gayaza Road in Wakiso district.

But the inevitable happened next. At just 14, she was already carrying her first child.

According to her, the man responsible was nearly twice her age and married, and that when he learnt that she had become pregnant, he vanished — abandoning her in a small rented house that she and her now two-year-old baby call home.

Every day, with her child strapped tightly on her back, Jane makes the short trip to her rickety, makeshift shop to sell basic groceries to eke out a living.

“I have no choice,” she tells me, as she tries to hush her crying baby. “I am alone and cannot give up. God provides.”

‘Candidates of social protection’

For a child that she still is, Jane’s tone of resignation to her predicament speaks directly to the sort of life many others like her are leading. But where do they sit in Uganda’s social protection system?

Children, youths, women, people with disabilities (PWDs) and the elderly fall under the vulnerable category, and as such need social protection safety nets. For instance, older persons (aged 80 and above) get a monthly grant of sh25,000 in the form of Social Assistance Grants for Empowerment (SAGE) — given on a quarterly basis. This programme currently reaches about 307,000 persons, according to the gender ministry.

Uganda put in place a social protection policy in 2015, which has been supported by the five-year National Social Protection Strategy (launched in 2024).

But is such a policy and related interventions effective?

"Yes, we have the policies and some interventions, but the operationalization of the life cycle is what is still lacking,” said Paul Onapa, the deputy head of the Expanding Social Protection Programme at the gender ministry, during a roundtable dialogue on the state of social protection in Uganda last Friday (February 21) in Kampala.

“Our interventions are supposed to provide safeguards that at any one point in life that you fall into, you are protected. But we don't see that covered,” he said at the event organized by the International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW).

A senior social policy and development professional, Onapa (pictured above R) said that although the Ugandan economy is dominated by the informal sector (over 78 per cent), the system in place is configured for the formal sector.

Here, investment is key.

“It is the responsibility of government to look after its citizens. Therefore, it is the government to put in the resources to finance social protection. Currently, the government spends 0.7% of our GDP on social protection,” said Onapa.

“Recently, we are seeing the global challenges in the funding space have driven and sunk many people into vulnerability. People who have lost jobs are now candidates of social protection.”

In light of the many threats (COVID, Ebola, etc), Onapa underlined that “we need to reconfigure our social protection architecture and systems to be shock-responsive so that when these things happen, we can be able to tap and hold Ugandans at that point of need”.

Last year, the government launched The State of Social Protection in Uganda 2024 Report, with it gives a mapping of where the country is in terms of delivering social protection for the poor and vulnerable.

Onapa said studies have shown that the investment in social protection has benefits at household, community and national levels.

Giving an example of SAGE and pointing to the report, he said "we registered an 11% decline in poverty among the beneficiaries".

Still, he spoke of the need to increase the amount from the current sh25,000 per month.

Meanwhile, the Sub-Saharan Africa average for at least one person to be covered by at least one social protection is 17 percent. But the current coverage in Uganda is a distant 6 percent.

"That means that as a nation, comparatively with our peers, we are way behind," said Onapa.

"The NDP IV target is to move this to at least 10 per cent. To achieve this, we need to hold our country accountable for the commitments that we make. So the issue is not the economics. The issue is the political will to look after your poor and vulnerable."

‘Strengthen the system’

In the context of social protection, public expenditure on the part of government is very important.

“Minus money, you are talking to yourself,” Dr Fred K. Muhumuza, a senior lecturer of economics at Makerere University Business School (MUBS), candidly put it.

Weighing in as a panellist in Friday’s dialogue, he said giving money to the around 34 percent of Ugandans living on roughly a dollar (sh3,600) a day may not be the ideal thing to do.

“Simply strengthen the system,” said Muhumuza (pictured below C), who is also the MUBS Economics Forum director. “One, let them earn their little money, but then make sure the little money they have earned is not spent on things government can cover.”

Pointing to budgetary priorities, Muhumuza desires a system that ensures free healthcare and education to relieve people of out-of-pocket expenses on such services.

"Right now, parents are selling Parish Development Model (PDM) projects to take children back to school.”

While Muhumuza agreed that the policy is the best social protection we have, he said “we can't operationalize it”, adding that what is needed are the basics.

According to him, many Ugandans are now surviving on social networks for social protection — to, for instance, ask colleagues for help, guidance, etc.

“Even SACCOs that were purely for lending have now created a window for emergencies: Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs).”

‘Tools responding to different problem’

But in all this, are the laws doing enough?

“The first challenge I see is we have failed to frame or determine who the vulnerable are in an effective manner,” said Moses Segawa (pictured below C), an advocate of the High Court of Uganda.

The problem of teenage pregnancies means that many mothers, like Jane of Kitetika, are children — a substantial demographic of Uganda’s population.

Under the Employment Act, paid maternity leave — as a social protection tool — is the legal response to motherhood.

“But instead, that teen mother is supposed to be in school,” said Segawa. “The question is: is she accessing the maternity leave right? Most likely not because she has not yet accessed the labour market.”

Additionally, many of the existing laws on social protection, like the Employment Act, assume that one has a job.

“The social security safety net really only responds to those in the labour sector: pension for the elderly (government), NSSF Act, etc. The coverage is so small,” said Segawa, a specialist employment and employee benefits practitioner.

“The tools in the tool box are responding to a different problem. The Workers Compensation Act assumes you have a job and that your employer has paid for insurance. But even government does not provide for workers compensation.”

And Segawa believes the barriers are not legal.

“They are structural. Our economy is a subsistence and informal economy (78%) but these instruments are all assuming that we are in the formal sector.”

His suggestion is adjusting the policy.

“The policy has to be designed on the premise that social protection has to respond to how our society is structured. You can't assume that our society is structured like in the UK where most people are in the formal sector and then you legislate minimum wage, workers compensation, pension, etc.

“If most people are in the informal sector, then your restructuring has to respond to the informal or at least begin to work with the institutions which interact with those informal, like the cultural, religious and community leaders.”

Short life span

So where does Uganda’s private sector — which employs 2.5 million people and contributes 80% of the GDP — fit in all this social protection discussion?

Uganda may be one of the most entrepreneurial countries in Africa but there is a catch. The majority of the 1.1 million enterprises (according finance ministry data) do not last long.

The short life span of Ugandan businesses and inconsistent business performance influence the social protection of those involved.

“Thirty-eight percent of Ugandans are entrepreneurs but only 10 per cent of those businesses live to see their tenth birthday. Over 50 per cent don't see their fifth birthday,” said Grace Nshemeire Gwaku (pictured below), the chief operating officer of Private Sector Foundation Uganda (PSFU).

Such uncertainty and instability makes many small enterprises become averse to formalizing, which by extension, shuts out avenues for social protection.

Nshemeire said most employees in Uganda do not have contracts, which makes them vulnerable, with employers wielding the power to dismiss workers as and when they please and without benefits or compensation.

To solve this, she said the policy can make it mandatory for employers to have contracts in place.

The reality is that it is expensive for some of the businesses to invest in people.

It's no wonder, according to Nshemeire, that some businesses resist some of the social protection initiatives such as NSSF and medical insurance. On flipside, others may desire to do so but are undone by their low financial health.

Nonetheless, some companies provide provident funds, medical healthcare, paid maternity and paternity leave as well as mental health wellness initiatives.

“We are starting to see innovation from the private sector to take care of the employees and the vulnerable. We are also seeing a huge Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) agenda, which is stretching private sector players to invest in communities and help with the interventions around health, education areas,” said the PFSU COO.

Opportunities to formalize the informal sector exist, she added.

“For instance, instead of letting vendors occupy a street in the evening, build a structure. Allocate them a stall. You can give it to them on credit and tell them to pay for it in five years so that eventually they own it. But also, you have them in the system.”

According to Nshemeire, creating awareness is important too.

“For instance, if you told a boda boda rider who earns roughly sh20,000 to sh40,000 per day to put aside sh2,000 every day towards the education or medical of his child, that is roughly sh700,000 per year!”

Data is key

Meanwhile, civil society organizations (CSO), represented at the ICRW dialogue, play a vital role in promoting social protection.

Of the around 3,200 registered CSOs as of last year, about a half (1,557) were specifically doing work around social services and development, according to information from the NGO Forum.

"Many CSOs spread around the country are doing direct social service provision,” said Mercy Grace Munduru, the head of programme and fundraising at Action Aid International, Uganda.

One of such services is the gender-based violence (GBV) intervention.

The concern here though is that while statistics show that GBV is on the rise, there are only 18 GBV shelters across the country of 146 districts.

Heavily dependent on donor funding, these GBV protection facilities are run collaboratively with the gender ministry and CSOs directly.

"With the [civil society] sector under threat constantly, for example from funding, shrinking civic space, this is a service (GBV interventions) that is so vulnerable that is can easily shut down overnight,” said Munduru, a human rights lawyer and activist.

"Recently, when the USAID funding cut happened, two of the shelters that serve the highest population (one in Bwaise and the other in Mubende) that specifically also target HIV response, and sexual and reproductive health rights, had to shut down.

“If a foreign entity decides to suspend funds or aid today, we don't have a fallback position because that is not a sustainable intervention," said Munduru (pictured below).

Munduru spoke of civil society as being core on monitoring and evaluating social protection schemes, thanks to the sort of access they have to the latest monitoring, evaluating and learning tools.

“One of the key gaps we see in terms of social protection programmes is that many times, work around this sector is not informed by actual data,” she said.

“When we are looking at the gaps and presenting all this data, it must be also considerate of the gender aspects of social protection. Otherwise we miss the point. And that is where civil society becomes critical because they have access to these tools and capacity.”

CSOs are also seen as important in driving accountability through conversations around issues like the NSSF legislation, and budget tracking and monitoring.

"In this country, if you do not drive accountability, a lot of the public resources get lost in corruption and other vices that compromise the quality of services that the community receives,” said Munduru.

“Research provides critical data that is needed to drive advocacy for policy and also give us the status for social protection in the country. Without that data, we cannot demand for policy."

On top of “investing smartly”, the human rights lawyer recommended building the bridge between the private sector and civil society as a sustainable approach to social protection “because I know there are opportunities for us to direct investments from private sector to address key gaps in social protection”.

‘Social protection not a favour’

While offering her two cents on the multi-sectoral panel dissecting the social protection subject, Kyegegwa district Woman MP Flavia Kabahenda Rwabuhoro was keen to set the record straight.

"When we are talking about social protection, we are not talking about poverty. We are talking about vulnerability. Some of us may never be poor, but we are all vulnerable,” she said.

“When we talk about social protection, we are looking at preparing people for a constructive role, building their resilience to address inclusion and making sure we don't leave anyone behind.”

The ‘Leave no one behind’ theme is the central guiding principle of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), meaning that all efforts towards achieving the goals should prioritize reaching the most marginalized and vulnerable populations.

'Shock-responsive social protection'

Kabahenda (pictured above), who is also the chairperson of the Uganda Parliamentary Forum on Social Protection (UPFSP), says a lot of work lies ahead.

“We need to research, we need to redefine vulnerability against poverty. We need to rewire our systems to make sure that the interventions and policies are not only meant to be aspiring for ready-made policy solutions or resolutions.

She said new trends are pushing people further into vulnerability.

“We need to have our policies and interventions to identify trends. How is social protection going to play in this new economy where technology, globalization, competition, and deregulation are now the new trends? We need to prepare people to stand for the situations as they come.

“Social protection is not a favour – it is a human right. It is humanitarian and it requires that human rights approach – from birth to death."

In the context of social protection, Kabahenda said the government needs to plan for a growing older population.

The UN Status Report of 2017 indicates that between 2017 and 2050, the number of older persons in the developing world will be predicted to increase from 65.2 million to 2.1 billion.

Unlike in the past, women have learnt to give birth only when it is necessary and are keen on keeping their offspring numbers low, said the Kyegegwa legislator.

With 75 percent of Uganda’s population being dependants (older persons, PWDs, children and youths), and the dependency ratio “biting on all of us”, Kabahenda said interventions on social protection must be alive to this reality.

“We need shock-responsive social protection,” she said, pointing to the recent disasters in Kiteezi, Bududa and Kasese.

The Uganda Functional Difficulties Survey (UFDS) 2017 indicates that 12.4 percent of Ugandans (around six million) have some form of disability. And households with a member living with a disability are reported to spend 39 percent more than households without.

The study said PWDs are also disadvantaged when it comes to access to decent work.

During parliamentary discussions on the NSSF law, PWDs said that waiting to clock 45 years of age so as to access midterm becomes difficult. They argued that, for instance, if a PWD lost their job at the age of 30, it would become difficult to get another mainly due to discrimination.

Kabahenda’s Kyegegwa district has been a host of refugees since the 1960s. She said that 8 percent of the refugees are PWDs, of which 75 percent report limited access to humanitarian response.

In the area of skilling young people, the legislator called for conversations between educationists and employers to discuss the exact skills their jobs require in today’s competitive labour market.

Kabahenda also clarified that under the PDM, the loan-based livelihood programmes are not a social protection tool.

“Up to now, the 39 percent people living in abject poverty are not accessing PDM because of so many things that disadvantage them,” she said, giving an example of child-headed families.

“Funding on social protection has remained below 1 percent of the GDP even when the returns on investment are clear: that every coin you put on people will return much more.

"Maybe we need to sensitize the planners. Give them the realities as they are.”

Looking ahead, the MP said that in no time, Uganda will have to shift away from past approach of looking after older persons and instead establish care homes for this vulnerable demographic.

Mentioning that the Child Disability Grant has remained an unfunded priority, Kabahenda said there is urgent need for a child-sensitive social protection tool that will address matters of the vulnerabilities in children.

She also spoke of the Girls Empowerment Programme in Kampala Greater Metropolitan as a child-sensitive social protection intervention and NutriCash in West Nile (almost all of them are supported by the civil society), as well as the need to spread these out to other districts.

“Let us enhance the planned data collection for social registry as part of the single registry for transformative and impactful targeting.

Now that there is a National Social Protection Strategy, Kabahenda and co at the UPFSP want a law that will sanction and deal with those who will not comply in as far as social protection is concerned.

“Let us do strategic shifts in engaging partners to support rollouts and upcoming social protection programmes,” she said.

“Maybe we may have to come up with a certificate of compliance for every sector on social protection, the way we have a certificate of compliance on gender and equity.”

The lawmaker also called for the mainstreaming of complementary social protection in a deliberate manner through a means test, as well as harnessing traditional and community-based social protection by way of institutionalizing social workers.

Back in Kitetika, Jane typically retires for the day not quite sure what tomorrow will hold. Sometimes, she tells me, she manages a profit of as much as sh20,000. The very good days.

Other days, she can hardly make the sh7,000 that ICRW Uganda board chair Jackie Asiimwe (pictured below) said the vulnerable Ugandan has to survive on on a daily.

Meanwhile, in her closing remarks on Friday, ICRW Africa Director Evelyne Opondo (pictured below) thanked everyone for participating in the vibrant multi-faceted discussion on social protection that provided plenty of takeaways.

Opondo said they will draw up a summary of especially the recommendations by the resourceful cast of panellists and collate them to use in further research around social protection.

"As ICRW, we are committed to women economic empowerment and this is just one of the ways we create these platforms for dialogue and we try to get different angles into the conversation, which we then use to inform conversations not just in Uganda, but also at the regional level," she said.

GROUP PHOTO 📸